Foreign Exchange Rate Determination

Like almost anything else, the value of any currency is determined by supply and

demand. The greater the demand in relation to the supply, the greater the value,

and vice versa. This is true even when no foreign exchange is involved. For instance,

if a country never expands its money supply, then the money that is available becomes

more valuable as the economy expands. Thus, the price of individual items decreases,

which is deflation.

When the money supply expands faster than the economy, then money becomes less valuable.

It takes more money to purchase single items, leading to inflation. Thus,

the German mark became almost worthless after World War I, when the government simply

printed much more money to pay its bills, or when the United States printed more

money to pay for the Vietnam War, leading to significant inflation in the 1970’s.

Naturally, in foreign exchange, when currency of a particular country is plentiful,

it will have less value against other currencies, and vice versa.

Demand for the currency also affects the exchange rate. If 1 country pays a significantly

higher interest rate than another country, or has significantly more investment

opportunities or a more stable government, then that country’s currency will have

greater value than that of the other country.

Sometimes governments, usually through their central banks, will intervene to keep

currency pegged to another currency, as China keeps the yuan pegged to the United

States dollar (USD), but this is mostly accomplished by manipulating the supply

and demand.

But how does supply and demand actually establish the rate?

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

It would seem to make sense that the amount of currency in any country that can

buy a particular basket of goods and services should be equal to the amount of another

currency that can buy the same basket of goods. This is referred to as purchasing

power parity.

In most cases, it is difficult to determine purchasing power parity (PPP) around

the world. Nonetheless, the Economist.com has compiled a Big Mac Index, which shows

the prices of Big Macs at McDonalds located throughout the world, and shows, according

to this index, how much a currency is overvalued or undervalued compared to the

USD. This is just a rough measure, of course, since some costs, like rent and labor,

cannot traded and equalized easily. It also ignores capital flows across borders,

which is a much bigger determinant of currency exchange rates, especially within

a short time period.

Although purchasing power parity makes sense, it cannot really establish foreign

exchange rates, because of the difficulties in equalizing the rates if it should

be different from parity.

When the same goods or assets are sold in different markets for different prices,

then the goods or assets can be bought in the cheap market and sold in the more

expensive market for a virtually risk-free profit, which is known as arbitrage.

Arbitrage equalizes prices in different markets to within a narrow range. However,

sometimes the expense of transporting and selling the goods in the higher-price

market is greater than the price differential.

For instance, if it takes fewer U.S. dollars to buy a basket of goods than Euros

in Europe, then how can anyone take advantage of the difference? Someone might try

to buy the basket of goods from the United States and sell it in Europe. However,

transportation costs and taxes would reduce or eliminate any potential profits significantly.

Thus, there is a wide gap that cannot be closed by arbitrage, because of the expenses

of buying in 1 country, transporting it to another, then selling it there—at least

for most commodities, especially food and energy.

However, arbitrage works very well in currency trades.

Dealers in Currency—Market Makers

Most currency trades are now done over the Internet, where time and distance are

no barrier. When you buy or sell currency, you usually do so with a market maker

in that currency. There are many market makers for most currencies, especially the

major currencies. A market maker may deal in U.S. dollars and Euros, for instance,

purchasing and selling both currencies by publishing a bid/ask price for both currencies.

If the market maker starts getting a lot of dollars in exchange for Euros, he will

raise the ask price for Euros, and lower the bid price for dollars until the orders

start equalizing more. If he didn’t do this, he would soon run out of Euros and

be stuck with dollars. He would not be able to continue business since at the bid/ask

price that he established, he would not have any Euros to trade for dollars, which

the market is currently demanding. Thus, to stay in business he lowers his bid price

for dollars and increases his ask price for Euros. To replenish his supply of Euros,

he also raises his bid for them, and to get rid of the excess dollars that he accumulated,

he lowers his ask price for dollars. This is how supply and demand works with a

single market maker—but there are many of them located throughout the world.

Each market maker must maintain parity with other market makers in the same currencies—otherwise

arbitrageurs would buy, for instance, Euros from the market maker with a lower ask

price and sell it to another market maker with a higher bid, and would continue

doing so until the prices equalized to within transaction costs.

But what about market makers in different currencies?

Currency Cross Rates and Triangular Arbitrage in the FX Spot Market

Cross rates are the exchange rates of 1 currency with other currencies, and

those currencies with each other. Cross rates are equalized among all currencies

through a process called triangular arbitrage. Below is a table of key cross rates

of some major currencies.

|

Key Cross Rates for 5/14/2007. (Source: MarketWatch.com)

|

|

Currency

|

USD

|

GBP

|

EUR

|

JPY

|

|

USD

|

|

0.50443

|

0.73951

|

120.10500

|

|

GBP

|

1.98244

|

|

1.46603

|

238.10043

|

|

EUR

|

1.35225

|

0.68211

|

|

162.41160

|

|

JPY

|

0.83260

|

0.41999

|

0.61572

|

|

All currency quotes are given in pairs, and each pair can be expressed as a fraction.

To illustrate, if a Great Britain pound (GBP) is worth 1.98244 USD,

then this can be expressed as the fraction 1.98244 USD/1 GBP.

We also see from the above table that a Euro is worth 0.68211 GBP,

which can be expressed as 0.68211 GBP/1 EUR.

From these 2 fractions, we can calculate what the USD is worth in EUR.

|

EUR/USD =

|

1.98244 USD

|

X

|

.68211 GBP

|

= 1.3522421

|

|

1 GBP

|

1 EUR

|

GBP cancels out, resulting in a quote for dollars per Euro. As you can see, this

is very close to the actual quote, 1.35225, from the table

above. Because we are ignoring the bid/ask spread and transaction costs to simplify

the math in this example, there is no reason to believe that it would be exact.

It is also true that arbitrage is not a perfect equalizer because the market is

not perfectly efficient.

But what if these cross rates didn't equalize. Suppose, for instance, that 1

GBP was exactly equal to 2 USD, with all other cross rates remaining the same. Obviously,

the above equation would not hold, but it would present an arbitrage opportunity

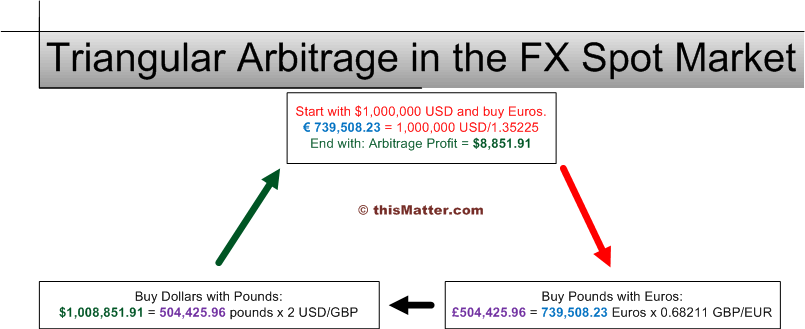

in the FX spot market, as illustrated below:

|

Start:

|

$1,000,000.00

|

USD

|

|

Buy Euros:

|

€ 739,508.23

|

= 1,000,000 USD/1.35225

|

|

Buy Pounds with Euros:

|

£504,425.96

|

= 739,508.23 Euros x 0.68211 GBP/EUR

|

|

Buy Dollars with Pounds:

|

$1,008,851.91

|

= 504,425.96 pounds x 2 USD/GBP

|

|

Arbitrage Profit =

|

$8,851.91

|

= $1,008,851.91 - $1,000,000.00

|

This can be illustrated graphically as a self-closing triangle of currency exchanges,

which is why it is called triangular arbitrage.

So, will you be able to profit from triangular arbitrage? Not likely. There are,

no doubt, many professionals and banks that have computers constantly calculating

the cross rates of all currencies. If there are any inequalities greater than transaction

costs, then they will be quick to close the gap, because if they don’t, someone

else will.

But triangular arbitrage does explain how the cross rates of currencies are kept

equalized.