Foreign Exchange Rates

Most common contact with foreign exchange occurs when we travel or buy things in

other countries. Suppose a U.S. tourist travelling in London wants to buy a sweater.

Price tag is 100 pounds (Symbol for pounds: £).

|

Current exchange rate

|

Price of sweater in dollars

|

|

$1.45 to £1

|

100 x 1.45 = $145.00

|

|

$1.30 to £1

|

100 x 1.30 = $130.00

|

|

$1.60 to £1

|

100 x 1.60 = $160.00

|

|

$2.00 to £1

|

100 x 2.00 = $200.00

|

For businesses or governments that trade billions of dollars, even small changes

in the exchange rate become significant.

When the United States dollar (symbol: USD) becomes stronger, then foreign goods

and services become cheaper, and goods and services from the United States will

become more expensive. Consequently, imports to the United States will increase

and exports will decrease.

When the dollar becomes weaker with respect to other currencies, then the opposite

happens: goods and services from the United States become cheaper, thereby increasing

exports, and foreign goods and services will become more expensive, thereby lessening

imports.

Thus, the trade balance of any country is largely determined by the value

of the domestic currency in relation to other currencies.

It would seem logical that if the dollar, for instance, weakens, the U.S. trade

balance will improve, as exports would rise and imports would decrease. However,

the U.S. trade balance usually worsens for a few months.

Most import/export orders are taken months in advance. Immediately after a currency’s

value drops, the volume of imports remains about the same, but the prices in terms

of the home currency rise. On the other hand, the value of the domestic exports

remains the same, and the difference in values worsens the trade balance until the

imports and exports adjust to the new exchange rates. This can be represented graphically

by the J-Curve:

The J-Curve depicts the lag between the currency depreciation

of a country and the improvement in its trade balance.

|

|

|

|

Source: New York Federal Reserve Bank.

|

Exchange rates are an important consideration when making international investment

decisions. The money invested overseas incurs an exchange rate risk.

When an investor decides to cash out, or bring his money home, any gains could be

magnified or wiped out depending on the change in the exchange rates in the interim.

Thus, changes in exchange rates can have many repercussions on an economy:

- Affects the prices of imported goods.

- Affects the overall level of price

and wage inflation.

- Influences tourism patterns.

- Will influence consumers’

buying decisions and investors’ long-term commitments.

Determination of Foreign Exchange Rates

Exchange rates respond directly to all sorts of events, both tangible and psychological:

- Business cycles;

- Balance of payments;

- Political developments;

- New tax laws;

- Stock market news;

- Inflationary expectations;

- Interest rate differentials;

- International

investment patterns;

- And government and central bank monetary policies among others.

At the heart of this complex market are the same forces of demand and supply that

determine the prices of goods and services in any free market. If at any given rate,

the demand for a currency is greater than its supply, its price will rise. If supply

exceeds demand, the price will fall.

The supply of a nation’s currency is influenced by that nation’s monetary authority,

which is usually its central bank. Government and central banks closely monitor

economic activity to keep money supply at a level appropriate to achieve their economic

goals. Too much money increases inflation, causing the value of the currency to

decline and prices to rise; whereas too little money can slow economic growth and

possibly cause rising unemployment.

Monetary authorities must decide whether economic conditions call for a larger or

smaller increase in the money supply.

Sources for currency demand on the FX market

The currency of a growing economy with relative price stability and a wide variety

of competitive goods and services will be more in demand than that of a country

in political turmoil, with high inflation and few marketable exports. Money will

flow to wherever it can get the highest return with the least risk. If a nation’s

financial instruments, such as stocks and bonds, offer relatively high rates of

return at relatively low risk, foreigners will demand its currency to invest in

them. FX traders speculate about how different events will move the exchange rates.

For example:

- News of political instability in other countries drives up demand for U.S. dollars

as investors are looking for a safe haven for their money.

- A country’s interest rates rise and its currency appreciates as foreign investors

seek higher returns than they can get in their own countries.

- Developing nations undertaking successful economic reforms may experience currency

appreciation as foreign investors seek new opportunities.

Theoretical Currency Exchange Rates

There are some who believe that some currency exchange rates are not what they should

be. For instance, there is a bill in Congress to correct any fundamental exchange

rate misalignment, a bill which is actually aimed at China because Congress

believes that the Chinese yuan is seriously undervalued against the United States

dollar. But how does one ascertain the misalignment of currency rates? Is there

a true exchange rate and can it be determined?

There are at least 3 methods that purport to reveal the true exchange rate, or to

at least reveal misalignments.

One common method is purchasing power parity (PPP), which is

the common assumption that the amount of currency needed to purchase a specified

basket of goods should be equal to any other currency needed to buy that same basket

of goods. However, this measure disregards the effects of comparative advantage,

which is the advantage that some countries have over others in producing a particular

product because of location or other factors. Moreover, purchasing power parity

is difficult to measure, although the Economist magazine publishes a

Big Mac Index, which is the price, in local currencies, to buy a Big Mac

hamburger at the many McDonald's restaurants located throughout the world, and compares

this to the United States dollar (USD). The Big Mac Index shows what the implied

PPP is in USD, which is equal to the price in local currency divided by the price

in the United States, and compares this to what the actual exchange rate is. None

of the exchange rates shown in the

latest index shows purchasing power parity, although some come close, which

could simply be a coincidence. Nonetheless, there are more sophisticated models

that purport to give a truer picture of PPP by accounting for differences in productivity

or income.

However, purchasing power parity does not account for international capital flow,

which is far more important in determining exchange rates. For instance, countries

with investments that yield the highest return will have large inflows of foreign

capital, which will certainly have an impact on exchange rates, but capital flows

are not related to PPP.

Another method to calculate what the exchange rate should be is the fundamental equilibrium

exchange rate (FEER), which is based on a sustainable current-account

balance and internal balance, with low inflation and full employment. A sustainable

current-account balance is predicated on the simple fact that a country

cannot continue accumulating more and more of a single currency unless it is actively

intervening to keep the exchange rate low. Thus, China's continually growing current-account

surplus of United States dollars is given as evidence that the yuan is seriously

undervalued. However, a large current-account surplus may result because the people

of a country invest more in foreign countries, or because the country has a low

interest rate. A good example of why the current-account balance could be misleading

is to examine why the Japanese yen is low compared to other currencies. The current

interest rate in Japan is about 0.5%, the lowest of the developed countries. Because

the interest rate is so low, and much higher elsewhere, many Japanese investors

invest their money outside of their country, but to do so, they must exchange Japanese

yen for other currencies. Another factor is the carry trade, where investors all

over the world borrow yen at the low interest rate, and convert it into currencies

where interest rates are higher, such as in New Zealand, which currently has an

interest rate of 8%.

Then there is the behavioral equilibrium exchange rate, which is predicated

on the invariance of cause and effect, so what economic variables influenced currency

exchange rates in the past, such as productivity growth or net foreign assets, will

also influence future currency exchange rates. While this seems plausible, how does

one determine that a particular set of variables and their relative importance determined

the exchange rate in the past? Will the importance of each economic variable change

when other variables change, and if so, how?

The Actual Determination, or Microeconomics, of Foreign Exchange Rates

- Microeconomics

- The study of a single economic unit, which may be a firm,

a household, or an organization. The interaction of all of these units is the purview

of macroeconomics.

- Rollover

- Swapping 1 forex contract for another with

a later delivery date, which is usually done because the trader who agreed to the

contract, does not actually want the delivery of the currency, but simply wants

to trade for profit.

While there are many theories about what actually sets the foreign exchange rate,

there is a simple way to visualize the true determiner of rates. Keep in mind that

banks do most of the actual trading and all of it is done in the over-the-counter

market, where 1 bank communicates with other traders, mostly banks to satisfy its

currency needs. You may be a forex trader trading with a broker, but that broker

trades with banks. Also, most forex trading done by retail traders does not actually

involve the transference of currency. The currency contracts are simply rolled over

into new contracts before actual delivery takes place. However, if you were a businessperson

or a government with a real need to trade actual currency, you would go to a bank

to satisfy your needs, because that's what banks do.

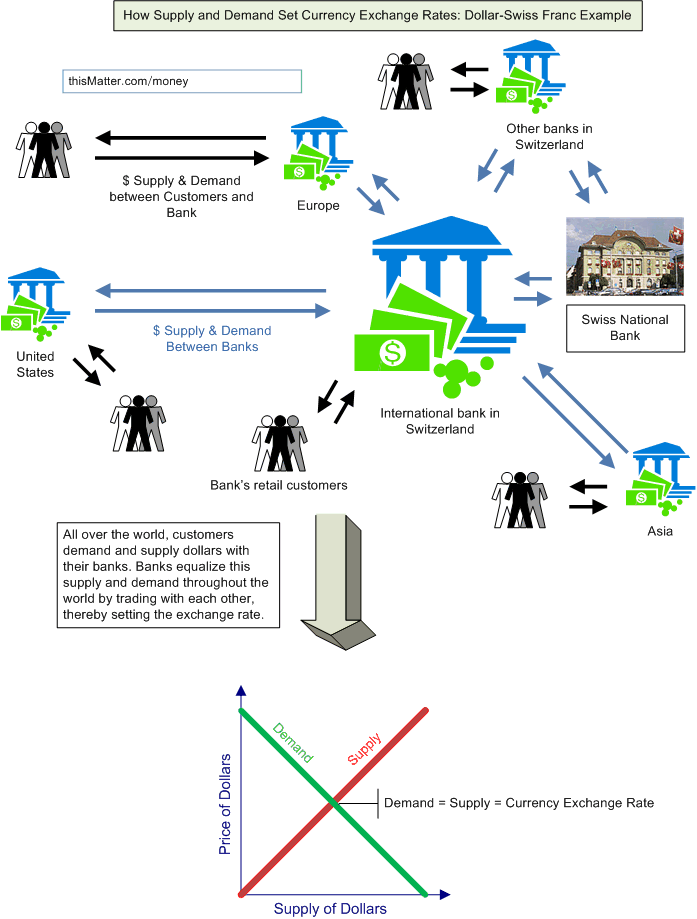

Now imagine that you owned an international bank in Switzerland. The main currency

of Switzerland is the Swiss franc (CHF), but since you are an international bank,

you must deal in other currencies as well. Let's take the United States dollar as

an example. Some of your customers will want to exchange francs for dollars, and

some will want dollars for francs. But how many dollars do you want to keep? You

want enough to satisfy your customers' need for dollars plus some reserves for unknown

immediate future demands.

Now, because an international bank actually needs different currencies to do business,

it will keep some of the dollars that it gets from customers so that it can give

other customers the dollars that they demand. But what happens when the bank starts

getting too many dollars in relation to that bank's customers' demand for dollars.

The simple solution is to simply reduce the price of the dollar in terms of Swiss

francs. When a customer comes in to exchange dollars for francs, you start giving

fewer francs per dollar. This immediately lowers the number of francs that your

bank pays for each dollar. Ergo, this lowers the exchange rate of dollars for francs.

But suppose you continue to get more dollars than you can use in your local business—maybe

because some local exporter has a hot new product that's selling wildly in the United

States, so the exporter has no choice but to trade dollars for francs, because he

has to pay his workers and suppliers in Swiss francs, since the business is in Switzerland.

As an international banker, you know that there are other banks that will have a

need for dollars, and so you call them, or communicate with them over an electronic

network, such as the Internet, and trade dollars for Swiss francs. You call another

bank in another town that happens to have a United States international firm doing

business in the town. While the business pays its local workers in francs and receives

revenues in francs, it needs to send dollars back home in the United States, so

it goes to the local bank to exchange francs for dollars. Because the bank doesn't

have enough dollars on hand to satisfy the U.S. business, that bank readily agrees

to exchange dollars for francs with your bank. You can also contact banks in New

York, some of which, will have a need for more francs than dollars.

But you also know that the Swiss government wants to keep the exchange rate of francs

for dollars low, so that exports to the United States increase and imports decrease,

so you contact the central bank of Switzerland, the Swiss National Bank.

To carry out the government's policy of lowering the exchange rate of the franc

against the dollar, the central bank agrees to buy your dollars for francs. If there

is no other need for the dollars, the central bank simply holds them in reserve

to satisfy the Swiss government's desire to lower the exchange rate of francs for

dollars.

Thus, the exchange rate that your bank sets will be determined by the total demand

from your customers and from other banks. But note that this exchange rate will

tend to be equal to the rate set by other banks. Why is this necessarily so? Remember,

the exchange rate that you set ultimately depends on demand on both your customers

and other banks that your bank trades with. If you are offering fewer dollars per

franc than other banks because of the excess of supply over demand from your customers,

then those banks will buy dollars from your bank until your rates become equal.

So this is how demand and supply actually work in the microeconomic view.

The demand and supply of currency ultimately originates with the people; even when

governments set monetary policy through their central banks, it is to satisfy the

needs of their residents; banks simply equalize this supply and demand all over

the world by trading with each other.

In the end, it could be concluded that the true currency exchange rate is what it

actually is.